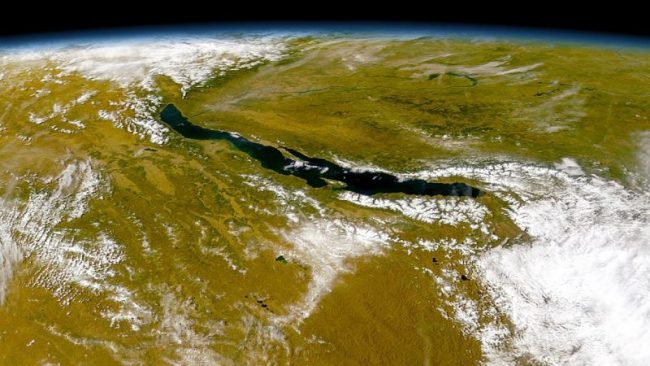

Russia’s Lake Baikal – in southern Siberia – the world’s oldest and deepest lake. Image via Yulia Starinova/RadioFreeEurope-RadioLiberty.

Around 25 million years ago, a fissure opened in the Eurasian continent and gave birth Lake Baikal, now the oldest lake in the world. It’s the world’s deepest lake, an estimated 5,387 feet deep (1,642 meters). Among freshwater lakes, it’s the largest in terms of volume, containing about 5,521 cubic miles of water (23,013 cubic kilometers), or approximately 20% of Earth’s fresh surface water. And – like many natural waterways on Earth today – Lake Baikal is the focus of ongoing controversies over development.

This ancient and deep lake is located near the Russian city of Irkutsk, one of the largest cities in Siberia with a little over half a million population according to a 2010 census. In the 1950s, the dam that made possible the Irkutsk Hydroelectric Power Station raised the water level in Lake Baikal by over a meter (several feet). This dam and its power station were heralded as:

… a Siberian miracle, a pearl of the Soviet water-power engineering.

Today, however, there’s more proposed development around Lake Baikal that’s not so universally admired. Environmental activists perceive various threats to the lake – for example, invasive algae along its coastlines – but the biggest perceived threat appears to be from Mongolian power companies that, with help from the World Bank, have been looking to build more hydroelectric dams near Lake Baikal. An April 2019 article at the website Rivers without Boundaries explained:

The Shuren Hydropower Plant, planned on the Selenga River in northern Mongolia, was first proposed in 2013 and is currently the subject of a World Bank-funded environmental and social impact assessment. In tandem, Mongolia is also considering building one of the world’s largest pipelines to transport water from the Orkhon River, one of the Selenga’s tributaries, to supply the miners in the Gobi desert 1,000 km (620 miles) away.

The ongoing environmental and social impact assessment began in 2017 and was expected to take three years, so there’s been something of a hiatus for those worried about Lake Baikal. But it’s a short hiatus, and a big worry. As RadioFreeEurope-RadioLiberty explained in 2017, as the new assessment was beginning:

… Mongolia’s project is far from dead. The Mongolian government has adopted the strategic goal of attaining energy independence from Russia, from which the country currently imports much of its electricity. In addition, China – eager to gain access to Mongolian coal – has pledged $1 billion in loans for the project. In fact, construction of power lines has already begun.

Why are environmentalists so worried about Lake Baikal?

Map via RadioFreeEurope-RadioLiberty.

The Selenga River, where the new power plant would be located, is a 600-mile river (nearly 1,000 km) that flows into Lake Baikal. It accounts for some 80 percent of the lake’s incoming water.

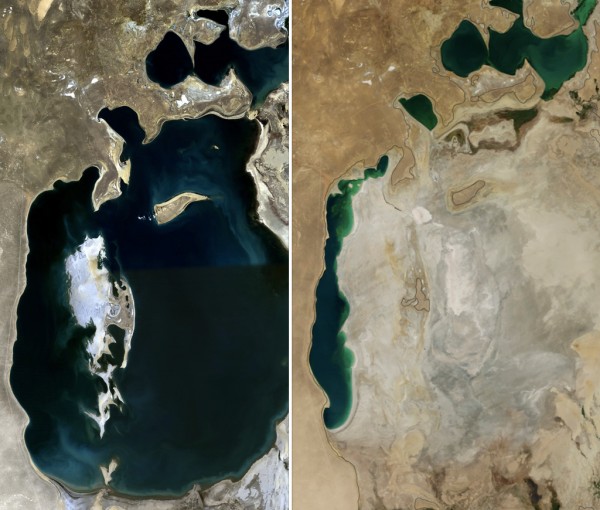

A strongly worded Siberian Times article published on May 25, 2016 spoke of an earlier ecological assessment of Lake Baikal. That assessment led to dire warnings that this lake could suffer the same fate as the Aral Sea, formerly one of the four largest lakes in the world, which began shrinking in the 1960s after the rivers that fed it were diverted by Soviet irrigation projects. By the late 1990s, the Aral Sea was less than 10 percent of its original size. According to the Siberian Times article:

Construction of … hydro power stations on the Selenga River and its tributaries can cause the unique lake [Baikal] to dry out. The 25 million-year-old lake is on the edge of environmental catastrophe and if certain measures are not taken, it might disappear just like the Aral Sea.

It’s hard to imagine the world’s deepest and largest lake disappearing due to human influence. Then again, it’s not hard to imagine a damaging environmental effect on a once-pristine natural area.

The Aral Sea in 1989 (l) and 2014 (r). Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Lake Baikal is currently a natural reservoir and a UNESCO world heritage site. It contains around 20 percent of the world’s unfrozen freshwater. In total, some 330 rivers and streams flow into Lake Baikal, some large like the Selenga and many small. Its main outflow is the Angara River. The water in the lake is said to be crystal clear, and some claim it has magical, mystical power. Those who want to preserve it point out that it is:

… the ‘Galapagos of Russia’ … its age and isolation have produced one of the world’s richest and most unusual freshwater faunas, which is of exceptional value to evolutionary science.

Holding one-fifth of Earth’s unfrozen fresh water, Lake Baikal is unlike other deep lakes in that it contains dissolved oxygen right down to the lake floor. That means creatures thrive at all depths in the lake. Most of Lake Baikal’s 2,500-plus species of plants and animals are found nowhere else in the world. Scientists believe up to 40 percent of the lake’s species haven’t been described yet. Species endemic to Lake Baikal have evolved over tens of thousands, perhaps millions, of years.

They occupy ecological niches that were undisturbed, until the last few decades.

The large freshwater seal indigenous to Lake Baikal, called a “nerpa.” Read more about the Lake Baikal seal at AskBaikal.

Lake Baikal’s unique biodiversity includes species like the Baikal seal, also known as nerpa. It’s the only mammal indigenous to Lake Baikal. In fact, scientists aren’t sure how these seals originally got into Lake Baikal. There are two primary hypotheses concerning this question, which you can read about here.

Another famous species native to Lake Baikal is the omul, a type of whitefish. It’s part of the salmon family. Local economies around Lake Baikal depend on this fish; it’s the main product found at local fisheries. Due to overfishing, it was listed as an endangered species in 2004.

On the far right side of this map, just above Mongolia, do you see the large blue crescent? That’s Lake Baikal. Map via Google.

By the way, even as humans vie for the opportunity to utilize the waterways around Lake Baikal – or protect them – over the long course of time, Mother Nature will also have its effect on the lake. The website Geology.com pointed out:

Lake Baikal is so deep because it is located in an active continental rift zone. The rift zone is widening at a rate of about 1 inch (2.5 cm) per year. As the rift grows wider, it also grows deeper through subsidence. So, Lake Baikal could grow wider and deeper in the future.

And so the saga of Lake Baikal continues …

Read more: Lake Baikal versus dams and pipelines, from Rivers without Boundaries.

Read more: Lake Baikal’s World Heritage Data Sheet

Read more: Rare animals of Lake Baikal

Lake Baikal seen from space. Image via the SeaWiFS Project, NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center, and ORBIMAGE.

Lake Baikal, via Flickr user Kyle Taylor.

Bottom line: Ancient and deep Lake Baikal is a a UNESCO world heritage site. Controversy surrounds construction of hydropower stations on a river that feeds the lake.

Source:

https://earthsky.org/earth/what-is-the-worlds-deepest-lake