Even the bright moonlight can’t diminish these bright stars. Icy moonlit trees and a lovely view of constellations Orion and Taurus, and the Pleiades star cluster, taken in early January 2017 by Cynthia Haithcock in North Carolina.

Look outside on a northern winter (southern summer) evening. You’ll see many bright stars. The evening sky also looks clearer and sharper than it did 6 months earlier, assuming no clouds are in the way. Why? On December, January and February evenings – in the course of our yearly orbit around the sun – our evening sky faces away from the center of our Milky Way galaxy, toward our galaxy’s outskirts. There are fewer stars between us and extragalactic space at this time of year. We’re also looking toward the spiral arm of the galaxy in which our sun resides – called the Orion Arm – and toward some gigantic stars located in this direction. These huge stars relatively close to us, within our own galactic neighborhood, our own local spiral arm, and so they look bright!

Consider the sky at the opposite time of year. In June, July and August, the evening sky seen from the entire Earth is facing toward the center of the Milky Way galaxy.

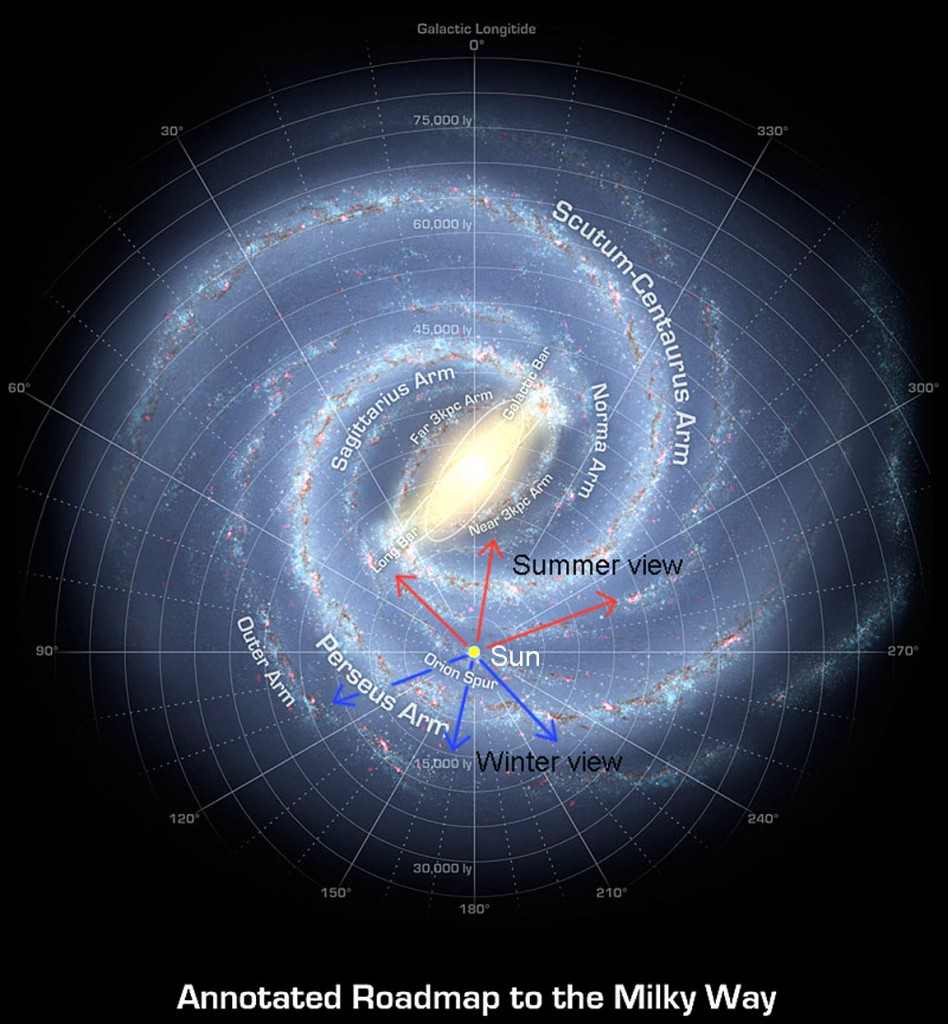

The galaxy is about 100,000 light-years across, and its center is some 25,000 to 28,000 light-years away from us here on Earth. We don’t see into the exact center of the Milky Way, because it’s obscured by galactic dust. But during those Northern Hemisphere summer months (Southern Hemisphere winter months), as we peer edgewise into the galaxy’s disk, we’re gazing across some 75,000 light-years of star-packed space (the distance between us and the center, plus the distance beyond the center to the other side of the galaxy).

Thus – on June, July and August evenings – we’re looking toward the combined light of billions upon billions of stars. The combined light of so many distant stars gives the sky a hazy quality.

EarthSky 2019 lunar calendars are cool! Order now. Going fast!

View larger. | On June, July and August evenings, we look toward the galaxy’s center, as indicated by the red arrows. On December, January and February evenings, we look away from the center, as indicated by the blue arrows. We’re seeing fewer stars now, and we’re looking into our local spiral arm. The overall effect is that the stars look brighter at this time of year. Artist’s concept via NASA/ JPL/ Caltech/ R.Hurt.

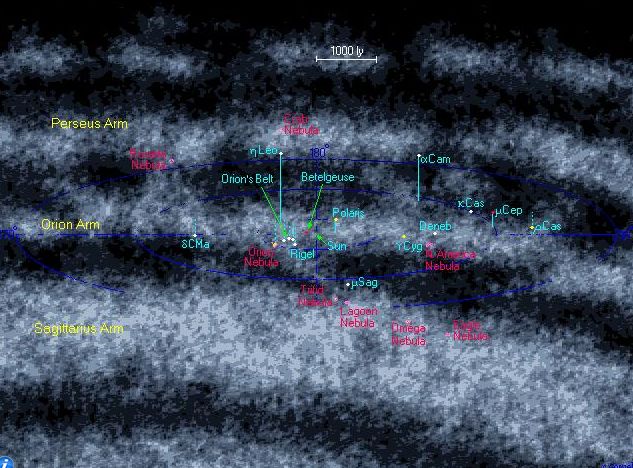

View larger. | Our local arm of the Milky Way galaxy is called the Orion Arm. Notice Orion’s Belt – which appears in our sky as three medium-bright stars (see photo below) – and notice Orion’s brightest stars Betelgeuse and Rigel. If you visit this page on Wikipedia, you’ll find this image in interactive form.

Our spiral arm of the galaxy is called the Orion Arm, or sometimes the Orion Spur. It’s not one of the primary spiral arms of the Milky Way but only a “minor” spiral arm. Our local Orion Arm is some 3,500 light-years across. It’s approximately 10,000 light-years in length. Our sun, the Earth, and all the other planets in our solar system reside within this Orion Arm. We’re located close to the inner rim of of this spiral arm, about halfway along its length.

The Orion Arm is also sometimes called the Local Arm, the Orion-Cygnus Arm, or the Local Spur.

Perhaps you know the bright stars of the prominent constellation Orion the Hunter? This constellation is visible in the evening during Northern Hemisphere winter (Southern Hemisphere summer). The stars of mighty Orion also reside within the Orion Arm of the Milky Way. In fact, our arm of the galaxy is named for this constellation.

Learn more about the sun’s place in the Orion Arm here

View larger. | Brightest star Sirius on left, with constellation Orion, much as you would see them on a December, January or February evening. Notice the short, straight row of three medium-bright stars: Orion’s Belt. The stars above and below the Belt are Betelgeuse and Rigel. Photo from EarthSky Facebook friend Susan Jensen in Odessa, Washington. Thank you, Susan.

Bottom line: The stars in the Northern Hemisphere’s winter sky look brighter – and the sky overall looks clearer (assuming there are no clouds) – because Earth is facing away from the galactic center and toward the depths of space.

Source:

https://earthsky.org/astronomy-essentials/star-seasonal-appearance-brightness