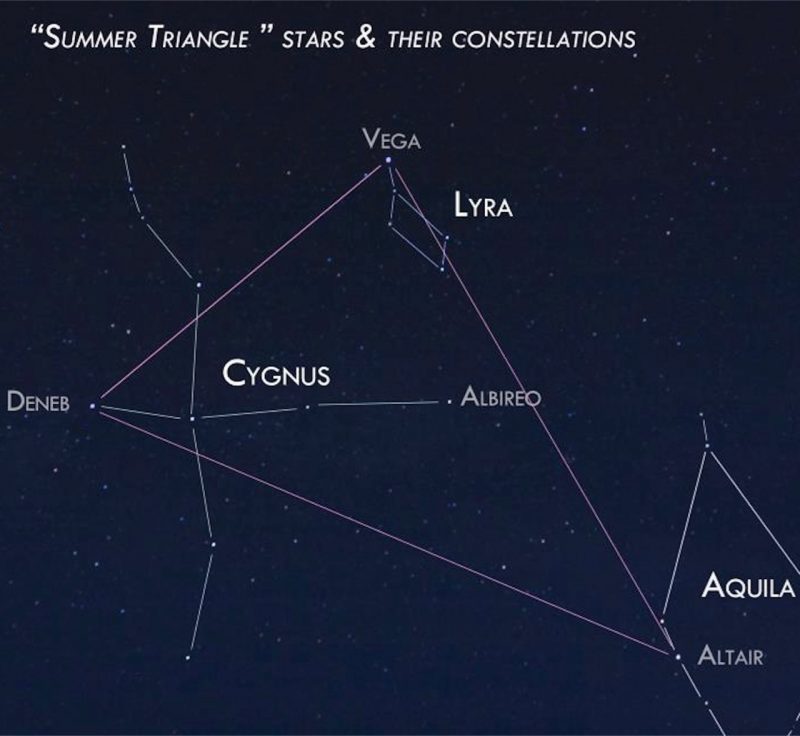

Sometimes several stars in different constellations join together to form a large asterism. That’s true of the Summer Triangle asterism, which is made of 3 bright stars – Vega, Deneb and Altair – in 3 different constellations. Image via our friend Susan Gies Jensen in Odessa, Washington.

What are constellations and asterisms?

A constellation is a recognized pattern of stars in the night sky. The word is from the Latin constellacio, meaning a set of stars. There are 88 official constellations. Many are very old. They’re a link between us and our ancestors, a projection of human imagination into the cosmos: ancient people looked at the stars and thought they saw mythical beings, beasts and cultural touchstones among the stars. On the other hand, most asterisms are relatively new. Most are small patterns within a constellation, although some are large patterns made of bright stars from several constellations. There’s nothing official about asterisms, but people on all parts of Earth still love them and enjoy them.

Stars in a constellation all lie at different distances from the Earth. For example, the three stars comprising the constellation of Triangulum are between 35 and 127 light-years away. While a constellation may look as if all of its stars are the same distance away, in reality that is only because, as we now know, stars vary in size and brightness, so two stars which appear to be the same brightness in the sky may actually be separated by vast distances. This means that an alien astronomer on a planet a hundred light years from Earth would know very different constellations, because they would see the night sky from a completely different perspective.

The Plough, for example, (also known as the Big Dipper or King Charles’ Wain) is a pattern of seven stars within the constellation of Ursa Major, the Great Bear. It is undoubtedly the most famous asterism in the sky, and not least because of its usefulness as a signpost for other stars and constellations. In the southern hemisphere, five stars comprise the Southern Cross, an asterism within the constellation of Crux. Sometimes, asterisms comprise stars of more than one constellation: for example, the glorious Summer Triangle, so prominent in the northern hemisphere sky between June and September, comprises stars in Cygnus, Lyra and Aquila. In Sagittarius there is the famous “teapot” asterism, inside which lies the location of the centre of our Milky Way galaxy.

There is no hard and fast rule for what constitutes an asterism: usually it’s a group of prominent stars in a simple pattern that are among the first that people recognise when they are learning their way around the sky.

Many constellations are well-known: Orion, Ursa Major, Cassiopeia, Cygnus , the famous star patterns you learn first when bitten by the bug of astronomy. But perhaps the most recognized are those that comprise the star signs of the zodiac: Aries, Libra, Pisces, Virgo and the eight others which had a special significance for astrologers, more than two thousand years ago when the first astrological charts were drawn by the Babylonians (although the history of the zodiac may go back further). The twelve constellations of the zodiac had a special significance because, together, they comprise the path through the heavens that the sun appears to follow during one year.

Of course, we now know that the sun does not follow this path, that it is the Earth which is moving and not the sun. We also know that since the first astrological charts were created, a gradual tilting of the Earth’s axis, causing an effect known as the precession of the equinoxes, means that the sun now appears to pass though a thirteenth constellation of the zodiac: that of Ophiuchus, the serpent-bearer. This has had the knock-on effect of changing the dates when the sun “passes through” each zodiacal constellation, so that, for example, Ophiuchus occupies most of the days in the calendar where the astrological sign of Sagittarius resides, and Aquarius largely occupies the space where Pisces is. Although this does of course invalidate the dates of the astrological star-signs seen in the horoscopes of tabloid newspapers, as well as the dates of the supposed star sign which people are “born under,” it should be remembered that the astrological zodiac has little resemblance to the actual constellations which the star signs represent: astrology simply divides the 360-degree heavens into twelve equal segments, without regard for how many degrees each constellation actually spans in the sky. This means that an astrological star sign can encompass more than one constellation, and therefore the astrological zodiac should be seen as largely symbolic rather than factual. It has nothing to do with the real universe.

It was the Greeks and Romans who, between them, first recognized and named the constellations of the Northern Hemisphere, listed around the second century A.D., although doubtless prehistoric humans had created their own constellations long before them. Indeed, each human culture has seen its own mythology and creation stories in the stars since time immemorial. Not surprisingly, the Greeks and Romans saw the heroes, heroines and beasts from their mythologies in the sky: Pegasus, Orion, Taurus, Cassiopeia and many others.

The first list of constellations we know of appears in Ptolemy’s second-century Almagest, which was his treatise on the apparent motions and stars and planets, and which established a geocentric view of the universe which was to persist for 1200 years. While the Greeks and Romans bequeathed us the names of the Northern Hemisphere constellations, it was Arabs who were the first to name the individual stars composing each: Islamic scholars were the first to systematically map the skies. Many of these Arabic star names have survived until today: Aldebaran, Alcor, Altair, Algol. The prefix “Al-” is a sure indication of an Islamic name: it simply means “the.” Hence, for example, Aldebaran is “the follower,” because it appears to follow the Hyades star cluster that makes up the head of the constellation of Taurus the Bull.

Certain constellations have acquired special significance over the millennia because of their appearance marking the onset of seasons, telling ancient peoples when to sow or reap their crops, when to collect food or animal skins. Because of the Earth’s orbit around the sun, different constellations become visible at different times of the year. For example, in the Northern Hemisphere the appearance of Orion in the early morning sky warns of the onset of autumn, that temperatures will shortly start to drop. The rising of the Summer Triangle to prominence in the northern sky is a harbinger of summer. Thus, to ancient cultures constellations were more than just patterns: they marked the passing of the seasons, of the years, of life itself.

The 48 constellations of the Northern Hemisphere, and their boundaries, were formally recognized by the International Astronomical Union in 1928 and the official list published in 1930. The story of the constellations of the Southern Hemisphere, however, is a little more complicated. Many of these were named by Italian, Dutch and Portuguese explorers of the 14th to 16th centuries. So as constellations there are objects and beasts associated with the great seafaring voyages of that epoch: Telescopium, the telescope; Octans, the octant; Dorado, the swordfish; Vela, the ship’s sails; Hydrus, the sea serpent. But explorers and observers often proposed different constellations with conflicting names, often to please their patrons. It was not until the 19th century that the current list of southern constellations was agreed upon and adopted.

From an observer’s perspective, from sunset to dawn the sky appears to revolve around one fixed point in the sky. This location in the heavens is what the Earth’s axis points at and is called the celestial pole. In the Northern Hemisphere, Polaris (the pole star) lies very close to the celestial pole, whereas in the Southern Hemisphere there is no bright star marking the location. Those constellations which revolve around the celestial pole yet do not dip below the horizon during the night, due to their proximity to it, are known as circumpolar constellations. In other words, for an observer these constellations will never set. There are five of these in the Northern Hemisphere: Ursa Major, Ursa Minor, Draco, Cassiopeia and Cepheus. The Southern Hemisphere has three: Crux, Centaurus and Carina.

The constellations are not difficult for a budding astronomer to learn. There are many excellent resources and planetarium-type programs available free online. It is certainly worth learning to recognize the constellations, even if sometimes we strain to see what the ancients did!

Bottom line: Constellations and asterisms are patterns of stars. Some asterisms consist of stars from different constellations, and some asterisms are part of one constellation.

Source:

https://earthsky.org/astronomy-essentials/definition-what-is-a-constellation-asterism