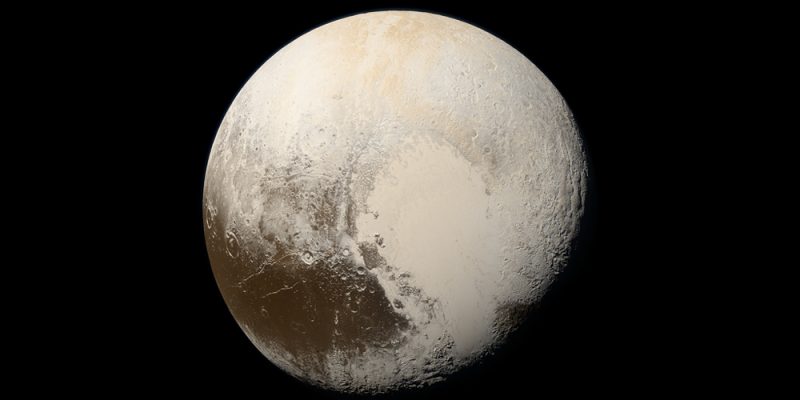

A natural color view of Pluto, as seen by NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft in 2015. The heart-shaped feature measures approximately 1,000 miles (1,600 km) across. Pluto is known to be made mostly of ices. New research – published in 2019 – adds to the evidence for a subsurface ocean beneath the dwarf planet’s icy outer crust. Image via NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute/Alex Parker.

July 14, 2015. NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft made its closest approach to distant Pluto on this date, sweeping only about 7,750 miles (12,500 km) above its surface (roughly the same distance as from New York to Mumbai, India). The fast-moving spacecraft had traveled almost 10 years and 3 billion miles (5 billion km) to that closest point at Pluto on our solar system’s outskirts. The entire long journey took only about one minute less than predicted when the craft was launched in January 2006. At Pluto, New Horizons “threaded a needle” through a 36-by-57 mile (60 by 90 kilometers) window in space; it was the equivalent of a commercial airliner arriving no more off target than the width of a tennis ball. New Horizons became the first-ever space mission to view Pluto and its moons (Charon, Nix, Hydra, Styx and Kerberos) up close. It’ll likely be the only space mission to Pluto in the lifetimes of many of us.

The Pluto story began early in the 20th century when young Clyde Tombaugh was given the task of looking for Planet X, theorized to exist beyond the orbit of Neptune. On February 18, 1930, he discovered a faint point of light that we now know as Pluto. Among New Horizons’ most immediate, stunning and visible findings was a bright heart-shaped feature on Pluto, which you can see at the photo at the top of this page. Scientists named it Tombaugh Regio after Clyde Tombaugh. Its nickname is simply The Heart.

Read more about The Heart on Pluto

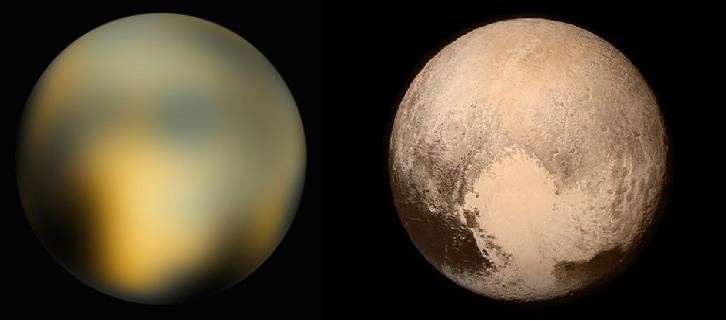

Best image of Pluto from Hubble Space Telescope (l) in contrast to a New Horizons image of Pluto. Scientists knew there was a large bright spot on Pluto, but it took a spacecraft flyby to reveal that bright spot as Pluto’s iconic Heart.

The NASA New Horizons Pluto Flyby team view the last image before the flyby of Pluto. Image via NASA.

LOCKED! We have confirmation of a successful #PlutoFlyby. pic.twitter.com/Krfo9qxxHw

— NASA New Horizons (@NASANewHorizons) July 15, 2015

//platform.twitter.com/widgets.js

Consider that our solar system consists of four rocky inner planets (Earth, Mars, Venus and Mercury) and four outer gas giants (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune). In the terminology of astronomers, Pluto and its largest moon, Charon, belong to a third category known as ice dwarfs, or plutoids. These outer worlds have solid surfaces like the inner planets, or like the moons of the outer planets. But they are made mostly of ices. When the New Horizons mission was being planned, it was a high priority for NASA to learn about the outer ice dwarfs in our solar system’s Kuiper Belt, which is an outer region populated by icy objects ranging in size from boulders to dwarf planets like Pluto.

New Horizons is the only spacecraft so far to obtain images from objects in the Kuiper Belt. It showed us that – like the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, the Kuiper Belt is populated by objects made individual by their unique environments and evolutions. For example, another stunning finding of New Horizons was that of ice mountains on Pluto, with peaks jutting as high as 11,000 feet (3,500 meters) above Pluto’s surface, along an equatorial region near the base of The Heart. Scientists quickly realized that these mountains on Pluto likely formed no more than 100 million years ago, making them extremely young in contrast to the 4.56-billion-year age of our solar system. Jeff Moore, a New Horizons imaging team member, commented at the time:

This is one of the youngest surfaces we’ve ever seen in the solar system.

And it’s still true. This finding from New Horizons suggests that this region on Pluto, which covers about one percent of Pluto’s surface, may still be geologically active today.

Read more about mountains on Pluto

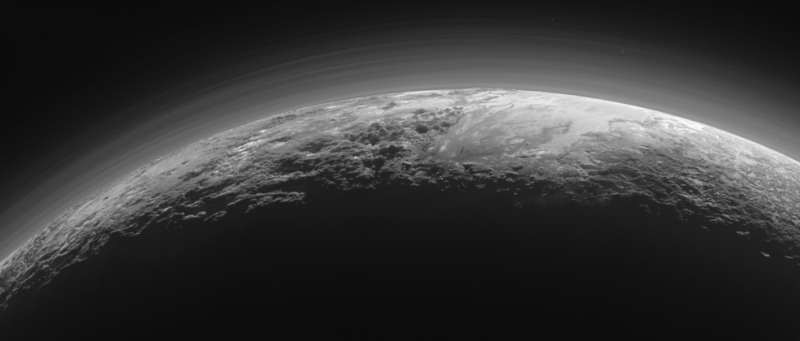

New Horizons images of a region near Pluto’s equator revealed a range of young mountains rising as high as 11,000 feet (3,500 meters) above the surface of the icy body. Scientists base the youthful age estimate on the lack of craters in the image above. Like the rest of Pluto, this region would presumably have been pummeled by space debris for billions of years and would have once been heavily cratered — unless recent activity had given the region a facelift, erasing those pockmarks. Image via NASA/ JHU APL/ SwRI.

New Horizons captured this image 15 minutes after its closest approach to Pluto on July 14, 2015, as it looked back toward the sun. The image was taken from a distance of 11,000 miles (18,000 km) to Pluto; the scene is 780 miles (1,250 km) wide. The backlighting highlights over a dozen layers of haze in Pluto’s tenuous but distended atmosphere. You can see Pluto’s rugged, icy mountains and the flat ice plains extending to Pluto’s horizon. The smooth expanse of the informally named icy plain Sputnik Planitia (right) – part of Pluto’s Heart – is flanked to the west (left) by rugged mountains up to 11,000 feet (3,500 meters) high, including the informally named Tenzing Montes in the foreground and Hillary Montes on the skyline. To the right, east of Sputnik, rougher terrain is cut by apparent glaciers. Image via NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI.

A year after the New Horizons flyby, the mission’s principal investigator Alan Stern of the Southwest Research Institute, Boulder, Colorado, listed the mission’s most surprising and amazing findings:

– The complexity of Pluto and its satellites is far beyond what we expected.

– The degree of current activity on Pluto’s surface and the youth of some surfaces on Pluto are simply astounding.

– Pluto’s atmospheric hazes and lower-than-predicted atmospheric escape rate upended all of the pre-flyby models.

– Charon’s enormous equatorial extensional tectonic belt hints at the freezing of a former water ice ocean inside Charon in the distant past. Other evidence found by New Horizons indicates Pluto could well have an internal water-ice ocean today.

– All of Pluto’s moons that can be age-dated by surface craters have the same, ancient age – adding weight to the theory that they were formed together in a single collision between Pluto and another planet in the Kuiper Belt long ago.

– Charon’s dark red polar cap is unprecedented in the solar system and may be the result of atmospheric gases that escaped Pluto and then accreted on Charon’s surface.

– Pluto’s vast 1,000-kilometer-wide (620-mile-wide) heart-shaped nitrogen glacier (informally called Sputnik Planitia) that New Horizons discovered is the largest known glacier in the solar system.

– Pluto shows evidence of vast changes in atmospheric pressure and, possibly, past presence of running or standing liquid volatiles on its surface – something only seen elsewhere on Earth, Mars and Saturn’s moon Titan in our solar system.

– The lack of additional Pluto satellites beyond what was discovered before New Horizons was unexpected.

– Pluto’s atmosphere is blue. Who knew?

At that time, Hal Weaver, New Horizons project scientist from the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland, commented:

It’s strange to think that only a year ago, we still had no real idea of what the Pluto system was like. But it didn’t take long for us to realize Pluto was something special, and like nothing we ever could have expected. We’ve been astounded by the beauty and complexity of Pluto and its moons and we’re excited about the discoveries still to come.

If you asked these scientists today – years after the flyby – I think they’d express a lot of that same excitement.

New Horizons is still speeding outward in our solar system. In early 2019, it encountered a second Kuiper Belt object, officially known as 2014 MU69 and nicknamed Ultima Thule. Read more about the Ultima Thule encounter here.

Team leader Alan Stern has said there is potential for a third flyby of a Kuiper Belt object by New Horizons in the 2020s. But, as yet, a suitable Kuiper belt object – close enough to the spacecraft’s current trajectory – still needs to be confirmed.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8ywbQ5L7mQ0&w=800&h=450]

Science team members react to the latest image of Pluto at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Lab on July 10, 2015. Left to right: Cathy Olkin, Jason Cook, Alan Stern, Will Grundy, Casey Lisse, and Carly Howett. Image via Michael Soluri.

The “blue skies of Pluto” as seen by New Horizons after closest approach, with Pluto backlit by the sun. It is one of the most iconic images of the mission. Image via NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI.

Bottom line: The New Horizons spacecraft’s flyby of the Pluto system was on July 14, 2015.

Top 10 pics from the Pluto flyby

View all images of the Pluto encounter from the LORRI imager on New Horizons

Enjoying EarthSky? Sign up for our free daily newsletter today!

Source:

https://earthsky.org/space/july-4-2015-new-horizons-at-pluto